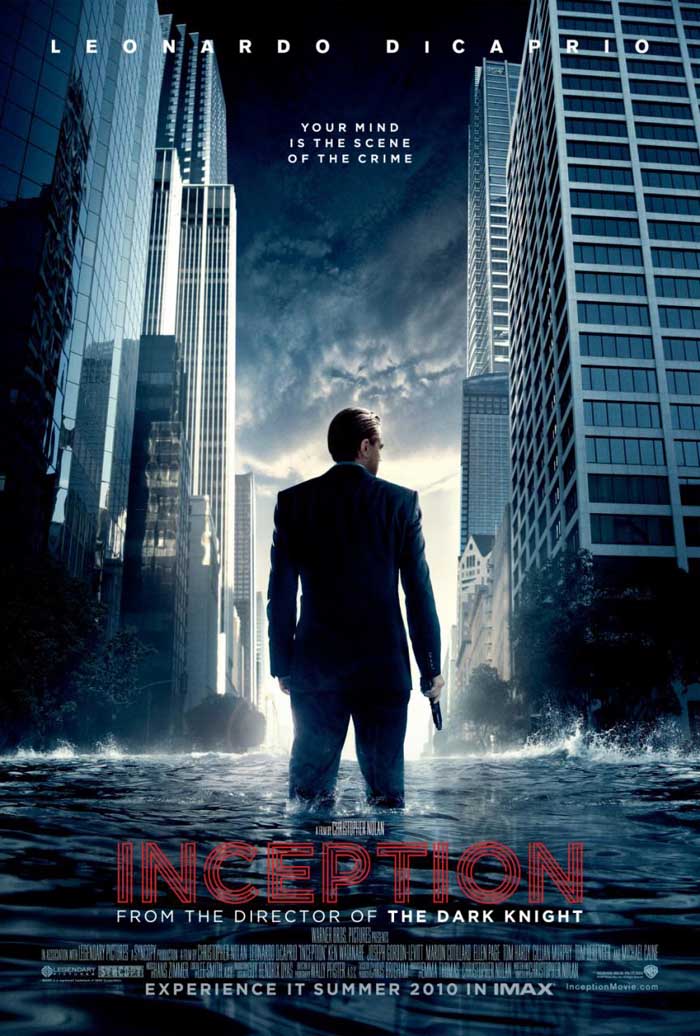

Deeper Into Movies: “Inception” (2010)

Inception is, in many ways, the anti-Matrix. Its protagonists are not reality-warping superheroes; it offers no tangled web of religious ideologies to make sense of. Its characters are not grappling with fate, but serving their own purposes. And yet, it gives us worlds within worlds, real and unreal, dreams and waking life and what lies beneath both. In some ways, The Matrix is its better: Inception‘s action, a barrage of anonymous gunshots and punches, lacks the visual invention of the Wachowskis’ bullet-time or even the balletic choreography of the Bourne trilogy. But Inception, full of it as it may be, is not an action movie. It is a heist movie, a suspenseful one, and also a love story, set against the backdrop of complex hard science-fiction that requires one’s full mental energy. Inception is a thinking person’s summer blockbuster, if only because it requires you to pay attention: do so, and the dots will connect themselves.

Inception is, in many ways, the anti-Matrix. Its protagonists are not reality-warping superheroes; it offers no tangled web of religious ideologies to make sense of. Its characters are not grappling with fate, but serving their own purposes. And yet, it gives us worlds within worlds, real and unreal, dreams and waking life and what lies beneath both. In some ways, The Matrix is its better: Inception‘s action, a barrage of anonymous gunshots and punches, lacks the visual invention of the Wachowskis’ bullet-time or even the balletic choreography of the Bourne trilogy. But Inception, full of it as it may be, is not an action movie. It is a heist movie, a suspenseful one, and also a love story, set against the backdrop of complex hard science-fiction that requires one’s full mental energy. Inception is a thinking person’s summer blockbuster, if only because it requires you to pay attention: do so, and the dots will connect themselves.

The story tells itself better than I could, so I’ll spare you the details. But Inception, while not quite the masterwork of director Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, finds the writer-creator delivering his most direct, emotionally resonant statement. In The Dark Knight and its directorial predecessor, The Prestige, the characters concluded the films by spitting out terse proclamations of their motives, gruffly outlining Nolan’s themes — not the screenwriter cardinal sin of talking the plot, but perhaps a worse one: unearthing the subtext. His reliance on such oral deliveries reappears here, but in Inception‘s world, the key lines are evocative, almost poetic — they feel revelatory instead of the opposite. This is largely the product of the love story, a complicated, beautifully visualized relationship that finds Leonardo DiCaprio’s troubled Cobb examining who, exactly, Marion Cottilard’s Mal is to him through the lens of his own subconscious.

In its third act, Inception stretches the suspense’s elasticity almost to the breaking point, but the film’s brilliant last shot is well worth the effort. The film makes necessary compromises: it builds a world (a half-dozen of them, really) without an origin story and lets it run wild, which leaves much of it still mysterious (though vastly more believable than anything from Lost). It is, for better (mostly, this) or worse, a Christopher Nolan movie, one both as visionary and limited as his imagination. One can only wonder if he dreams of electric sheep.